American Louis Sullivan, mentor to Frank Lloyd Wright, has been called "the father of Modernism" and "the father of the skyscraper". He is credited for the well known modernist design credo: "Form follows function". Taken out of context and revised, this idea is often misunderstood. Here is the whole statement:

It is the pervading law of all things organic and inorganic, of all things physical and metaphysical, of all things human, and all things super-human, of all true manifestations of the head, of the heart, of the soul, that the life is recognizable in its expression, that form ever follows function. This is the law.'[8]

Sullivan, in turn, attributes the idea to a Roman architect and engineer named Marcus Vitruvius Pollio. Around 20 B.C. Vitruvius wrote De architectura, the oldest surviving treatise on architecture. In it he declares (in Latin) that structures must be solid, useful and beautiful. There seems to be plenty of room for argument in favor of ornamentation in the interpretation of beautiful.

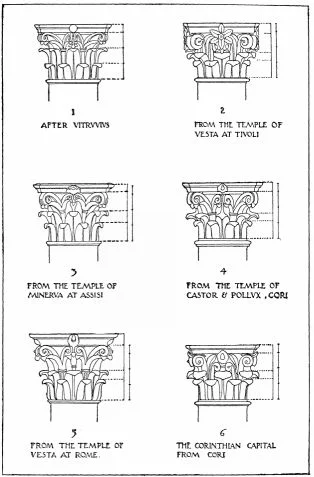

How did Vitruvius interpret this credo? Looking at his comprehensive work, De architectura, by beautiful, he means well proportioned, after the human body, using the rules of the classic temples of Rome and Greece. The decorations at the top and bottoms of columns and elsewhere are described as elements imitating nature, earlier building techniques or attempts to cover features that were considered unattractive.

from De architectura

Like William Morris who once wrote “Nothing useless can be truly beautiful” and then went on to design decorative wallpaper, stained glass, and ornate textiles for most of his life, Sullivan decorated his buildings with complex ornate motifs that became his signature but certainly went well beyond simple utility.

Frank Lloyd Wright modified Sullivan's statement for his own use by stating that "Form and function are one". Wright loved to embellish too though. Most of his work is rooted in pragmatism but when we think of his contribution to architecture, we can't avoid the images of his famous motifs rendered in stained-glass or textile block.

And then there was Adolf Loos, an architect who born in Austria in 1870 just three years after Frank Lloyd Wright was born in the United States. Loos delivered a lecture titled Ornament and Crime in 1910 directly attacking the use of ornament in the arts using moral and evolutionary arguments. "The evolution of culture marches with the elimination of ornament from useful objects"

Loos practiced what he preached. The radically innovative Loos House below was not consistent with the fashions of the period and was criticised by some. Planters were added to the window sills as a result a disagreement with the client. His simple pragmatic work was a true reflection of his values against the opposition of traditional opinion. With or without acknowledging it, all Modernists are indebted to his uncompromised genius.

Loos House, 1910 (aka the house without eyebrows)

Bedroom of the Kraus home by Adolf Loos, Photo by Pilsen-Tourism

Click on the title to comment on this or any of our posts.