“The future is already here – it's just not evenly distributed.”

―William Gibson

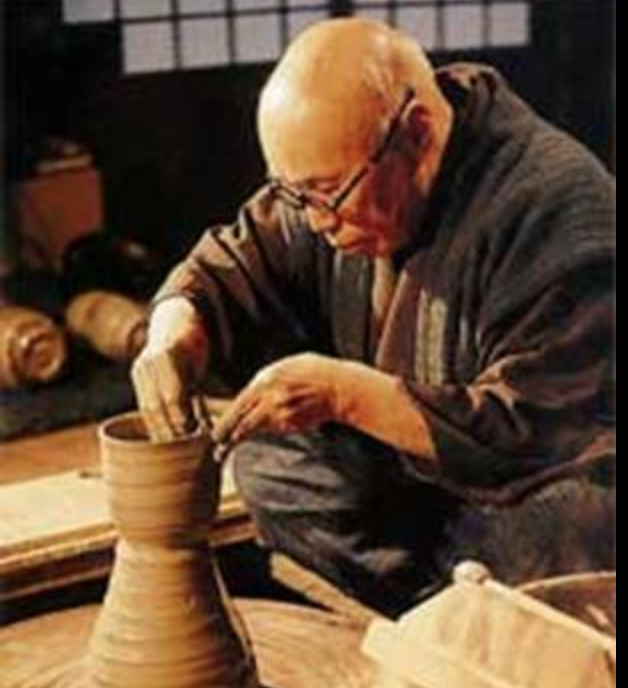

To me, Modernism isn’t a style. It’s a philosophy, a set of values, not a look. It’s good design. It’s the future. It is an idea that perhaps always has been and hopefully always will be. What about traditional Japanese, Danish or Shaker craft is not Modern? Form follows function. All these “styles” share a rational pragmatism, contempt for waste, and absence of decoration. Form follows function embodied.

The conclusions we draw from modern values change as each generation discovers it anew in a fresh landscape. We interpret it in the context of the new knowledge and tools not available previously. Our environment is always changing so the best design solution is a moving target between what is possible and what is available. We shouldn’t strive to move beyond Modernism but instead to embody it in our time. The biggest changes we have seen this century revolve around improving sustainability.

With the hindsight of 50 or more years, Can you parse the treasure from the trash of the past? Each year that goes by reveals new information about the appropriateness of materials and processes.

Buckminster Fuller was interested in the concept of embodied energy but didn’t have the information he needed to inform his decisions. The high cost of aluminum doomed his Dymaxium house before embodied energy even had a chance to. Nobody is building houses out of aluminum today because it’s a terrible material choice due to the energy/cost as well as it’s undesirable thermal properties. To be fair, this wasn’t as clear in 1930-1945 when he was working on it.

Modern production today includes, where possible, favoring the use of wood and other natural fibers that capture carbon and eventually bio-degrade. Considering the energy consumed in shipping materials and products and the potential of human exploitation are also becoming part of the modern math. Not to mention the social costs of our separation from the process and makers of the goods we buy.

In the end, what is Modernism but human design mimicking natural design. As in nature, the part of Modernism that we get right will survive and multiply. The things that we get wrong will not. Novelty, trends and fashion fool us for a moment but efficacious and efficient solutions rule the day. Suitability to task is the compass heading and The Kingdom of Beauty is our destination.