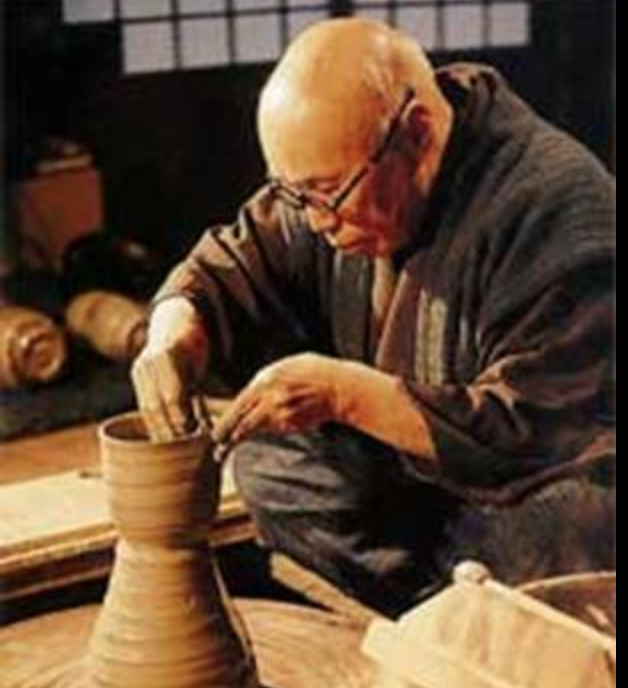

Shoji Hamada, 1894-1978

What is the difference between Industrial and craft objects? Is it the manner in which they were made?; By hand or by machine? Almost all the things found in folkcraft museums are “handmade” but on closer examination you will discover that many are products of a combination of hand and machine work. After all, a potter’s wheel is a machine as is the weavers loom and the woodworkers lathe. So it is not simply the machine that differentiates industrial goods from craft goods.

From Wikipedia:

Industrial design is a process of design applied to products that are to be manufactured through techniques of mass production.[2][3] Its key characteristic is that design is separated from manufacture: the creative act of determining and defining a product's form and features takes place in advance of the physical act of making a product, which consists purely of repeated, often automated, replication.[4][5] This distinguishes industrial design from craft-based design, where the form of the product is determined by the product's creator at the time of its creation.[6]

Modern tools like an injection molding machine nearly completely eliminate the human role in the production of products In this process the machine is not easily adaptable and renders a unchanging and uniform product. No room for the surprising small mutation that turns out to be better than the status quo.

Craftsmen have been using machines for centuries to make objects of incredible utility and beauty. The defining characteristic lost in the industrial revolution was that the form of the product was no longer determined by the product's creator at the time of its creation. Designing and making are divided. The cost of producing products plummeted but not without consequences. The craft version was more costly but it was the product of a living process. It was informed by the thousands of like objects that came before it and can spontaneously change to meet changing needs. Each pot that comes from a potter’s hands has the potential to be more suitable than it’s ancestors. In these items the form is determined by someone who has extensive and intimate understanding of history, process of making as well as the demands of the contemporary market. The industrial product is static. Unable to adapt quickly, it’s growth is stunted. We struggle to describe the loss using terms like “cold”.

The Dean of Modern American craft, Wharton Esherick had this to say about machines in his work:

“I use any damn machinery I can get hold of…Handcrafted has nothing to do with it. “I’ll use my teeth if I have to”

Wharton Esherick in Craft Horizons Magazine, 1966

And the man who codified the Laws of Craft Soetsu Yanagi also makes room for the machine.

“The machine, of course, came into being for man’s use and advantage; therefore, we need not avoid it but should find a way of using it more cleverly than we have done hitherto. The problem is not a matter of either hand or machine, but of utilizing both. We have yet to discover just what is suitable work for each….The best course, probably is that handwork and the machine should cooperate and supplement each other’s shortcomings. This has already happened in the industrial arts in Denmark.”

-Soetsu Yanagi from The Unknown Craftsman

It is not the hand that makes the craft but the connection between the designer and the making. As with all living things on this evolving planet, the unchanging is doomed to obsolescence. There is always a version that is more suitable to task in today’s fast-changing world so let’s keep looking for it while engaging more completely the process of making.